Running head: INSTRUCTOR-STUDENT PERSONALITIES

Instructor-Student Commonalities in the Martial Arts:

Leadership Traits and Similarities

Martin Thomas McGee

The personality

characteristics between martial-arts students, assistant instructors, and their

senior instructors were investigated. The participants come from seven various

martial arts schools in Illinois (n = 104). The types of martial arts schools

that participated included various forms of karate (e.g. Dentokan, Shotokan,

etc.) and Tae Kwon Do. The personality traits measured were locus of control

(LOC), need for cognition (NFC), goals and motivation (GM), and anxiety (ANX).

The previous traits listed could be associated with leadership qualities.

Findings suggest that there are no significant personality differences between

head instructors and assistant instructors. There are, however, significant

differences between head instructors and their students as well as assistant

instructors and students. These findings indicate the original hypothesis that

stated personalities become less varied in the higher levels the martial arts

social hierarchy is supported. Future applications and implications of this

research is relevant to understanding the dynamics within any type

super-ordinate/sub-ordinate relationship within hierarchal indoctrination-like

social systems.

A Brief History on Leadership

A leader, in general, is anyone that is looked up to. Usually, it is someone who outranks another in a hierarchy; it is someone who is in a super-ordinate position. This general definition is not limited to the President of the United States or other government positions but can cover a broad range of everyday relationships including teacher-student relationships, boss-employee relationships, coach-athlete relationships, etc. Much psychological research has been conducted focusing on leaders and leadership. Many have asked the following questions: 1) What psychological reasons do we choose certain leaders? 2) What makes us stay with someone who is a leader? And 3) Do leaders have anything in common? Many of these questions can be answered by looking at the history of the psychological study of leadership.

To better understand why it is important to look at the similarities between instructors and students, especially the leadership qualities within the dynamics of super-subordinate relationships, one should be briefed on the history of leadership studies. According to Kremer et al. (2003), many questions about leaders and leadership have socio-psychological roots that started in Victorian literature. During this era, literature described �great men� who were prominent figures in human history and world development. Kremer et al. (2003) continue by stating that this led to the development of �metatheory� - the belief that through meticulous experimentation and ardent research it would be possible to make general rules of behavior that dictate variable relationships. The goal of the �great man approach was to provide a formula� of physical and psychological attributes that would epitomize a quality leader.

Kremer et al. (2003) conclude their brief history by discussing the successor to metatheory, the zeitgeist. The zeitgeist approach suggests that strict formula approaches to leadership fail because leadership qualities are dependant upon historical and situational factors. The reasoning behind this approach is based on the failed meta-theory attempts to quantitatively create a formula that covers every leader in every situation.

Even within the same historical setting, it can be easily argued that an intellectually-gifted CEO that manages to get his or her company out of debt may not be the best candidate to fill a physically demanding military field officer position in the military. Although these are both very important positions that require leadership, it is obvious that the required traits and attributes for each are different.

In more recent attempts to define leadership, during the First World War, researcher Bass (1990) states military leaders leaned on psychology in order to identify �potential leadership material.� Since the middle of the 20th century other variables have been researched in hopes of finding answers to psychology�s questions to leadership, including gender, gender role, and the type of material taught (Freeman, 1994).

Generalized Application of Leadership Traits

Studies in attempt to gain insight into leadership qualities have been long since sought after. Large quantities of psychological research have been conducted in attempts to figure out the defining characteristics of leaders or future leaders. Super-ordinate to sub-ordinate relationships are everywhere. Boss-employee, coach-athlete, and teacher student relationships are just to name a few. People are always trying to �get to the top.� Employees seek to become managers. Some college students go to graduate school and some even aspire to get their doctorate degrees. However, in order to climb any hierarchy, one is evaluated; super-ordinates are always looking for people with potential leadership capabilities.

In everyday job settings, human beings conduct their own small-scale evaluation of others trying to climb the corporate ladder - the interview. Humans are always evaluating one another, either unconsciously by social comparison or whenever one is trying to not promote an incompetent person to a level wherein a certain competency is required. However, in looking at the dynamics of the interview process a very important realization occurred.

Research by Breakwell (1990) suggested that the process of interviewing has become unreliable because of its internal, two-way dynamic interaction; the functionality of verbal and non-verbal cues, and the perception thereof, influences the outcome. What this means, in short, is the interview process is reflexive, or circular and two-way, and subjective. This makes sense, because both parties� communication, verbal and non-verbal, will have a direct effect on each other, and this impacts the subjective nature of the interview process. This subjectivism, however, exists in everyday communication as well, not just interviews. Therefore our perceptions are always playing a role in evaluating others. Even in martial arts, rank evaluations are subjective (Sylvia and Pindur, 1978).

Because communication can be subjective in nature, one�s perceptions become important in understanding what makes a good leader. For example, an interviewer, a manager at a prestigious hotel, is looking for someone to fulfill a leadership position. The interviewee for the position of assistant manager, in turn, looks up to the interviewer as a leader to model, imitate, etc. The interviewing manager will look for someone that people will follow and look up to. Because the interviewer will be someone who is looking for someone who is still going to be their subordinate in some way, shape, or form, they want someone who will respect and follow their every decision. Furthermore, the interviewee, who will become the interviewer�s subordinate, will take up the position if he or she feels that they are competent and can meet the demands of the future employer. Furthermore, he or she must be able to agree with the demands of the interviewer�s futures requests. Now, the question arises, �What motivates a person to become compliant to the requests of their super-ordinate?�

Field Theory On Personality

Kurt Lewin (1951) stated that behavior is a function of one�s environment, or simply put B = f (e). This is often cited as Lewin�s Field theory. Everything that goes on in one�s environment impacts his or her behavior. This environment can be a workplace, school setting, or just life at home. In certain settings, the environment can cause individuals to become compliant, face punishment, be promoted, or even withdraw.

One might ask the question, �What type environment can be researched that affects everyone�s behavior in the same way?� Obviously, there is boot camp, America�s most prevalent �status degradation ceremony� so-to-speak, but sometimes that is not so easy to study, unless one is in the military. However, a more easily accessible indoctrination process with a hierarchal structure exists where a personality change occurs for almost everyone along his or her path � a martial arts class. Here are the following reasons why:

1. Everyone begins with a white belt. This is the equivalent of losing one�s identity or the equivalent of having one�s head shaven or becoming just another �Private Pyles� in the military. One�s status has just been allocated to the lowest part of the hierarchy. In some schools, some instructors make students test for their white belt.

2. One�s rank is displayed for everyone else to see. It is obvious where one lies in the hierarchy, and they know it. Furthermore, one knows what they must do, and act like, to go up the ranks. At some schools, if one fails a rank test, it is possible to be demoted.

3. Every martial arts school has some sort of qualities/philosophy that is indoctrinated into their students. For example the Tae Kwon Do practitioner is the embodiment of the Tenants of Tae Kwon Do: Courtesy, Integrity, Perseverance, Self-Control, and the Indomitable Spirit. Often, these traits must be memorized and displayed for one to go up in the ranks.

4. Every student within a martial art does the same thing. Yes, some people train harder than others outside the martial arts school, but in the class everyone follows the training regimen, sometimes to the chief instructors count. For example, a hypothetical class schedule may be stretching followed by break-falls, basics, and then sparring. Any deviation or disrespect can lead to punishment (push-ups, laps, more grueling break-falls, or holding a static stance just to name a few) from his or her instructor.

5. Everyone listens to super-ordinate ranks. This is the natural order of hierarchies. Students listen to assistant instructor; assistant instructors listen to the head instructor.

6. Everyone imitates in the beginning. Although martial-artists become more innovative and creative due to their own personal tastes, physical attributes, and creativity, one must recognize the fact that everyone had to learn the same thing, the same basics. In martial arts classes, students imitate assistant instructors or the head instructor. This is usually done visually by participant observation. Bandura�s common knowledge on modeling indirectly suggests that we will model those who outrank us, especially in strict hierarchal systems like martial arts.

It is because of this hierarchal system within martial arts schools and other social settings, such as the military, work, and other administrations, that researchers can look at the important character traits of a leader, as specifically defined by the sensitivity of a job. The nature of these hierarchal, indoctrination systems is conducive to the commonality between the super-ordinate and sub-ordinate. In essence, this is more a zeitgeist than a metatheory approach when understanding leadership qualities in each different hierarchy.

Personality In Teaching.

Narrowing down the research, one can see how personality in super-ordinate and subordinate relationships has an effect on perceived effectiveness by a student. Sherman and Blackburn (1974) suggested that an instructor�s teaching characteristics are not nearly as important as his or her personality. Therefore, from a liking-similarity theoretical framework, which briefly states that we like those most similar to ourselves, that although someone may be an amazing martial arts instructor, if there is no congruence in similarity, a student may choose to withdraw from training with that instructor. So in time, those who are least like their head instructors may opt out of his or her classes.

Research by Hart and Driver (1978) asked the two following questions: �Do student evaluations differ as a function of differences in the instructors personalities?� and �Will students perceive teachers who are more like them in personality as being most effective?� Hart and Driver�s findings indicate that only their first hypothesis was supported but state �it would be worthwhile to make a comparison between the grades of students with different degrees of instructor-student similarity.�

Personality In the Martial Arts

Researcher Jorge Gleser (1988) coined the term the �Ju principle.� Ju is a Japanese syllable. Roughly translated it means �gentle.� For example judo means �gentle way� or aiki-jujitsu means �harmonious, gentle art.� Gleser�s ju principle is the idea of yielding, or being compliant, in psychotherapeutic practices. However, moving away from psychotherapy and focusing more on the martial art, Gleser alludes to the idea a person begins to embody values associated within his or her study of martial arts.

Weiser and Kutz (1995) state ��[martial arts] teach the values of directness and honesty in communication, assertiveness, ability to empathize, courage, humility, perseverance, gentleness, respect for others, responsibility, and self improvement.� Psychological benefits from martial arts are caused by the �confrontation of one�s self and others� (Spear, 1989). Attendance in a martial arts class, therefore, has an effect on one�s personality. However, the effect can be positive or negative.

How Type of Training In Martial Arts Effects Personality

The effects from training in various martial arts have inherent physical and psychological effects. The effects of training reflect on the type of martial art and how it is practiced. Tai Chi is a �soft art� characterized by smooth, fluid, circular movements. In a study by Kutner et al. (1997), 200 participants were allocated into two different classes. One class was a Tai Chi class. The other class was an individualized balance training class. Follow-up research indicated that only participants in the Tai Chi class experienced an overall life change.

There is an irony to the above study. Tai Chi is currently practiced by an �older� population for its recently discovered health benefits. According to general Chinese medicine, Tai Chi has always had health benefits experienced by its practitioners. These benefits, which include lessened anxiety, flexibility, and longevity, are caused by a vital energy called chi, ki, or qi depending on the country of the Orient. Chi flows along meridians, or lines across the body; this flow of energy, in turn, affects one�s health. However, health-related practice is only one focus to Tai Chi. This current trend of �Tai Chi for health� focuses on the non-violent, peaceful application of the art and its practitioners, in turn, become non-violent and peaceful. Yet, there is another side.

According to some martial artists, Tai-Chi has a deadly application as well. Historically, this is supported by acupuncturist records of the Ming dynasty of China (McCarthy, 1995). Striking particular vital points of the body can lead to a quick or delayed death. This is not only applicable to Tai Chi, but any other combative martial art. Many people overlook the deadly application aspect of martial arts, especially Tai Chi.

If �soft arts� were taught like some �hard arts� where the emphasis was placed more on power, aggression, and how much damage one can inflict in one blow, would �soft art� stylists become more aggressive in their nature? Research (Davidson, as quoted from Goleman, 2002) suggests that personalities can be shifted to become more or less peacefully predispositioned by the things we do. Actions and feelings stimulate a shift in activity in our left and right prefrontal cortices. This in turn influences our emotion. Furthermore, because of neuroplasticity, a brain can be rewired to be prone to a certain emotion. Therefore, the way we train in martial arts affects our personality and our leadership qualities. According to Freeman (1994), the values and qualities one experiences becomes a model for the student that is applied to other aspects of his or her life.

Influence of Hierarchy and Leadership in Martial Arts

Authors (Biddle and Thomas,

1966) say that people will adopt behaviors and attitudes from those who are in

the same role. Sylvia and Pindur (1978) state that we will mimic the attitudes,

skills, values and techniques of those who are more experienced within the same

social hierarchy. Sylvia and Pindur (1978) continue by stating, �Role learning

is affected by situational characteristics.� Findings by Sylvia and Pindur

(1978) suggest that there is a strong, significant correlation between the

attitudes of students and their instructors.

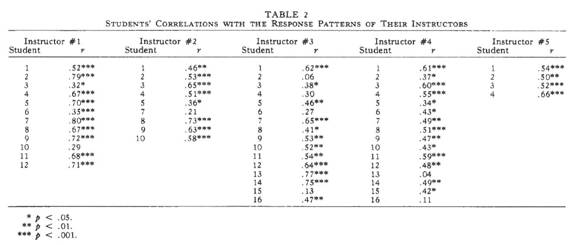

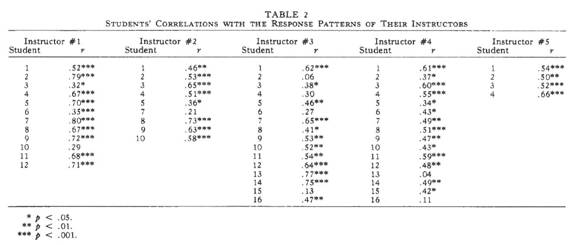

**Sylvia and Pindur on Correlation of Response Patterns on Attitude Questionnaire

In a rigid social hierarchy, like martial arts, it would make sense that people would become more similar as a function of time, because everyone�s situational experience is relatively the same within the dojo. However, this hypothesis is not supported by Sylvia and Pindur (1978). Their findings suggest state that socialization takes place early and is independent of time and rank.

Martial arts schools are hierarchal, indoctrination-like social systems. Because of their rigidity, participants share the same experiences. Also, during this same time, modeling of super-ordinate positions occurs. These in-class experiences and modeling yield similar personalities among members. These similar personalities contain leadership qualities, such as a high need for cognition, strong locus of control, and strong motivation. Due to the subjective and reflexive nature of evaluation, those who have leadership qualities most similar to their instructors will be promoted to the next rank. Those who lack leadership qualities similar to their instructor will not be promoted. Not being promoted has nothing to do with being liked by the instructor, but not being qualified by displaying the attitude of one who is to be promoted to a higher rank. Or, because of this lack of attitude similarity as perceived by the student, there are differences in values that cause him or her to withdraw from classes. Hence, time �weeds out� those who are dissimilar from their instructor. Below is an illustration:

Similarity Perpetuates Itself/Leadership Qualities Reinforced

Person Similar � Promotion

Modeling of Higher Ranks

Person Dissimilar � Withdrawal

Person Recycled/Relearning of Qualities

Participants were administered a 28-question personality survey based on a 7-point Likert scale. The survey was broken up into four sections excluding demographic information. Part one�s focus was internal locus of control (LOC), or how much responsibility one places on him or herself (Weiner, 1974; modified by Eggleston, 2000). Part two�s focus was need for cognition (NFC) which is how much one likes to think (Eggleston, 2000). Part three involved goals and motivation (GM) (Eggleston, 2000). Part four�s focus was anxiety (ANX) (Burns, 1993).

Procedure

After its first field test, the survey was modified and truncated. Next, the survey was field tested on a 12-year-old martial arts student, after the parental consent form was signed. The only explanation needed by the 12-year-old was an explanation of a Likert scale. The survey only took 7 minutes for the karate student to complete. Students under the age of 18 were given consent forms to be signed by their parents or guardian. Then surveys were administered at seven area martial arts schools and collected by the researcher. The four sections and the title of the survey were deceptively titled to avoid demand characteristics. Instructors were informed of this deception ahead of time. Instructors debriefed students after surveys were administered. Data from each dojo (martial arts school) was analyzed using SPSS.

Participants in Dojo A (n = 22) were martial arts students enrolled in an instructors track Tae Kwon Do class. T-tests were run to determine the significant differences between instructors, assistant instructors, and students.

T-tests run on internal locus of control (LOC) revealed that there was no significant difference between the head instructor and assistant instructors (t = .203; p = .852). Although not significant, t-tests reveal that there is less similarity between the head instructor and the students (t = 1.009; p = .328) than between the instructor and assistant instructors. Furthermore, the least similarity lies between the assistant instructors and the students (t = 1.165; p = .123).

T-tests run on need for cognition (NFC) reveal assistant instructors as having more similarities to students than the head instructor (p = .955 > p = .062). There was a significant difference between the head instructor and the students (t = 2.279; p = .037).

T-tests run on goals and motivation (GM) revealed no significant differences. However, there was a greater difference between the head instructor and his or her students (t = 1.299; p = .285) than the head instructor and the assistant instructors (t = 1.299; p = .212).

T-tests run on anxiety (ANX) revealed no significant differences. When comparing the head instructor to the students, the most notable, but insignificant, difference occurs (t = -2.048; p = .057).

Graph of Means for Dojo A (n = 22)

|

LOC � Locus of Control NFC � Need for Cognition GM � Goals and Motivation ANX - Anxiety |

A graph of the means best illustrates whom the assistant instructors are more similar to. In the case of Dojo A, assistant instructors are more similar to the head instructor in terms of internal locus of control and anxiety levels. However, assistant instructors are more similar the students in terms of need for cognition as well as goals and motivation.

Results for Dojo B

Dojo B is a karate class held within a church. This class is not an instructors track course. But it could be argued that all martial arts courses could be instructor-track oriented, because students strive to attain their black belt. T-tests run on Dojo B were conducted in the same manner as Dojo A.

T-tests run on LOC revealed that there was no significant difference between the head instructor and assistant instructors (t = 1.440; p = .245). Although not significant, t-tests revealed that there was the most similarity between the assistant instructor and the students (t = .465; p = .647).

T-tests conducted on NFC indicate that assistant instructors are more similar to the students than the head instructor (p = .991 > p = .233).

GM t-tests indicated that assistant instructors and the head instructors have a very similar levels of motivation and goal oriented behavior (x1 = 42.0, x2 = 41.8; p =.938). There were no significant differences, but the means suggest the hypothesized direction.

T-tests run on ANX indicated no significant differences among the three positions. However, the means suggest the predicted direction of the hypothesis.

|

LOC � Locus of Control NFC � Need for Cognition GM � Goals and Motivation ANX - Anxiety |

In the case of Dojo B, assistant instructors� means are most similar to the head instructor in terms of goals and motivation and anxiety levels. However, assistant instructors are more similar the students in terms of internal locus of control, and need for cognition.

Results for Dojo C

Dojo C is a martial arts school located near a state university campus. It has the most participants of any of the single martial art schools that participated. However, the lack of assistant instructors led to insufficient data to run t-tests between the head instructor and assistant instructor. There was only one participant who achieved the status of assistant instructor.

T-tests that were completed indicated that there were no significant differences in any of the four personality traits between the head instructor and students as well as the assistant instructor and the students. However, the means for anxiety fell in the predicted direction. Much of the data for this dojo is inconclusive and incomplete due to the lack of participants in the assistant instructor category.

|

LOC � Locus of Control NFC � Need for Cognition GM � Goals and Motivation ANX - Anxiety |

Dojo C�s results, although having the largest population of the single dojos, may have been skewed because there was only one assistant instructor. Regardless, the means for anxiety fell in the predicted direction.

Cumulative Results

After all the data was entered into SPSS, and all the single schools with an n ≥ 20 were analyzed, every participant�s questionnaires were used in a cumulative study. Data analysis was conducted the same way as single martial arts schools.

LOC t-tests indicated a significant difference between the assistant instructors and students (t = 1.995; p = .049). Furthermore, p-values and means indicated that assistant instructors similar to the composite scores of seven, head instructors.

NFC t-tests indicated no significant differences among the head instructors, assistant instructors, and students. However, p-values and means indicated that assistant instructors were least similar to students (t = 2.016; p = .051).

T-tests run on GM indicated a significant difference between the assistant instructors and students (t = 4.232; p = .0001). Furthermore, data indicated head instructors were significantly different from students (t = 2.012; p = .047). There was no significant difference between the head instructors and the assistant instructors (t = .279; p = .783).

T-test run on ANX indicated no difference between the head instructors and assistant instructors (t = -1.381; p = .180). There was a significant difference in anxiety between assistant instructors and students (t = -2.849; p = .006). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in anxiety between the head instructor and the students (t = -2.968; p = .004).

|

LOC � Locus of Control NFC � Need for Cognition GM � Goals and Motivation ANX - Anxiety |

In the larger, cumulative sample, assistant instructors� means are more similar to the mean head instructors� composite score in three out of four personality categories. The composite assistant instructors means score was closer to the mean composite score of all the student participants in the need for cognition category. However, all means did fall in the predicted direction.

Discussion

Results of this experiment are semi-supportive of the original hypothesis. Although few significant differences were found, means for Dojo A, Dojo B, and cumulative means were in the predicted direction indicated in the hypothesis. For example, Dojo A�s students had the lowest average need for cognition (x = 35.6). The assistant instructors NFC average was 35.8. The head instructor�s NFC average was the highest at 48.0. The instructors� NFC average is also above the entire group average (x = 36.2), the students� averages lies below, and the assistant instructors� averages somewhere in between that of the students and the head instructor. The position of the means for locus of control and goals and motivation follow the same pattern. Dojo C is the outlier in this case, but its inconsistency is caused by the lack of assistant instructor participants.

When looking at anxiety, the order is reversed; the instructor has the lowest ANX score below the group ANX mean and the students� mean always above the group ANX mean. This suggests that martial arts can contribute to stress-management.

Were the assistant instructors more like the head instructors or the students? When looking at individual martial arts schools, the similarity of assistant instructors varied. However, with the larger, cumulative sample, research indicates that assistant instructor personalities are more similar to the head instructor personalities with the exception of NFC scores. Again, findings were in the direction predicted.

The cumulative t-tests indicate something that contradicts the original hypothesis. Assistant instructors are more significantly different to students than are the head instructors. Common reasoning suggests that the head instructors would differ the most from students, not the assistant instructors. However, the modeling of students and the creativity of assistant instructors can explain this contradiction. In the lower ranks, novice martial artists mimic everything � movements and personality traits. This is done in an attempt to fit into the social hierarchy and, in turn, highly resemble the head instructor.

However, as a student becomes more competent, he or she may become an assistant instructor. It is at this point a martial artist realizes a very important aspect to his or her training. A martial art is a combative art form, one that is open to personal interpretation and independent thought. A student realizes that due to body type, physical capabilities, and physical limitations that what works for his or her instructor may not personally work for them. Also, during this time, an assistant is usually encouraged by his or her instructor to engage in activities by which interpretation and application of martial arts movements is part of training and evaluation. These conditions of capabilities and personal interpretation put an assistant instructor on a totally different level than the student that is still modeling the head instructor. This might explain why assistant instructors differ more from students than the head instructors.

Future Implications & Considerations

Sample sizes of the single martial arts schools analyzed should be larger. However, this is a difficult task in a rural private/commercial martial arts schools. Had this research been done on the East Coast where martial arts schools are more prevalent and have a large student population, then the research would have yielded more accurate results.

Perhaps different personality traits could have been analyzed. Locus of control, need for cognition, goals and motivation, and anxiety are important leadership traits. However, other personality characteristics like aggression, humbleness, and perception of others could be analyzed.

Future implications of this study could be applied to any super-ordinate to sub-ordinate relationship. Within martial arts schools there is a relatively large time away from class and, therefore, a lot more time to be affected by external factors. Perhaps more significant results would be found in more controlled environments like the military, communal societies (e.g. the Oneidans), gangs, or cults.

Bass, B.M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill�s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research and Managerial Applications. (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press

Biddle, B.J. & Thomas, E. J. (1966) Eds. Role Theory: Concepts and Research. New York: Wiley

Breakwell, G.M. (1990). Interviewing. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

Burns, D.D. (1993). Ten Days To Self Esteem. New York: Quill William Morrow

Freeman, H.R. (1994). Student Evaluations of College instructors: Effects of Type of Course Taught, Instructor Gender and Gender role, and Student Gender. Journal of Educational Psychology. Vol. 86 (4), December 1994, pp. 627-630. Retrieved March 21, 2005, from PsycARTICLES database.

Driver, J. & Hart, J. (1978). Teacher Evaluation as a Function of Student and Instructor Personality. Teaching of Psychology. Vol. 5 (4) December 1994, , p198, 3p. Retrieved March 21, 2005, from Academic Search Premier

Glasser, J. (1988). Judo Principles and Practices: Applications to Conflict-Solving Strategies in Psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, Vol. 42 (3), July 1988. pp. 437-447

Goleman, D. (2003). Destructive Emotions: And How We Can Overcome Them. London, England: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. P. 12

McCarthy, P. (1995). The Bible of Karate: Bubishi. Boston, MA: Tuttle Publishing. P. 109

Sherman, B., & Blackburn, R. (1974) Personal Characteristics and Teaching Effectiveness of College Faculty. ERIC Document. 9, 088313

Kremer, J., Muldoon, O., Reilly, J., Sheehy, N., & Trew, K. (2003). Applying Social Psychology. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan

Kutner et al. (1997). Self-Report Benefits of Tai Chi Practice By Older Adults. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences &Social Sciences, Vol. 52B (5), September 1997. pp. 242-246

Lewin, K. (1951). Field Theory in Social Science. New York: Harper.

Spear, R.K. (1989). Military Physical and Psychological Conditioning: Comparison of Four Physical Training Systems. Journal of the International Council for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 25, pp 30-32

Sylvia, R.D. & Pindur, W. (1978). The Role of Leadership In Norm Socializations in voluntary Organizations. Journal of Psychology. November 1978. Vol. 100 (2). P. 215, 12 p

Weiner, B. (1974). Achievement motivation and attribution theory. Morristown , N.J. : General Learning Press.

Weiser, M. & Kutz, I. (1995). Psychotherapeutic aspects of the Martial Arts. American Journal of Psychotherapy. Vol. 49 (1). P. 118, 10 p

©